| [ Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec ] |

||||

|

||||

Writing on the WallI first encountered Paul in the fall of 1968 when my family took possession of his

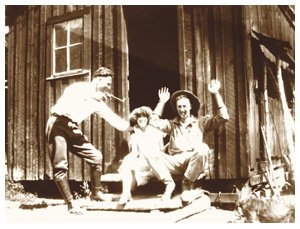

The three-story log cabin had been Paul’s parents’ house, built in the mining town of Marble, Colorado. In 1939, at the age of 43, Paul took the house apart, piece by piece, and rebuilt it up on “the ranch”, the family’s homestead property. It is the house that Paul built – nothing about it is thoughtless or mass produced. There are pyramid blocks in every corner to blunt the angle for easier sweeping. The built-in, breakfast nook table is hinged to the wall, allowing it to be raised up and cleaned under. The walls are unpainted panels of wood that tinge the light with their honey color, and there is writing on them. In various places you come across it. Some of it illegible. Some upside down. But the piece that reached out and grabbed us, that set us humming, is on the wall in the room under the attic stairs. It’s a guest list. The heading reads: Annual Duck Dinner 1909. The second name on the list is LP Montgomery, my great-great-grandmother. It seems that for a few years in the early 1900’s she was the school teacher in the booming town of Marble. She had been a guest in the house that was then Paul’s parents’ house. Seeing her name written so clear and bold on that list, we knew it was right for us to be there, that we were welcome to bring the raucous chaos of our living into the quiet there, to take up the position of Paul’s descendants. We were the closest there was. When we came upon it, the house was essentially

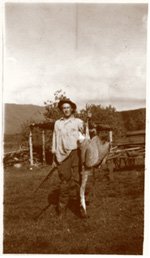

We began to listen, and to collect the stories of Paul’s life. We listened to his house and the things he made and the things he kept by him. We listened to the landscape he inhabited, the closeness of it – mouse and fly, dirt and rock, wind across the water, the sudden approach of storm, the relentless white of winter, the abyss of a moonless sky. We listened too, to the talk of friends and neighbors who survived him. All of these sources speak of self-reliance, resourcefullness, a certain humor, a certain moodiness, hope, disappointment, lonliness.

I think about the stories Paul wrote with his life, stories written in wood and pipe, stone and paper, stories that sat unread for 17 years after his death, and might have gone on infintely unread until they sank back into the stuff of earth they were pulled from. Paul’s stories might never have been attended, except that, by fate and circumstance, my family came to read them, to play them out and absorb them into ourselves. I think about how we have listened, how we have dwealt within the stories of Paul and listened with such intent that for thirty years we have resisted making changes to his house. We took offense when others suggested upgrading. We didn’t want to change things. We were listening. Last year, my brother transcribed some of Paul’s diaries and I read them for the first time as an adult. I was struck by the regular rhythm of them, the steady heartbeat of his days, and moved to respond in kind, to answer the stuff of his life with the stuff of mine, day by day. That’s what this is, this book of days, a duet between Paul and I, across cultures and landscapes and 84 years. It is my writing on the wall. I do not expect a large audience. It is enough that the possibility exists that someday someone will stumble upon it, and in reading, begin to resonate. January 1, 2001 Lisa B. King |

||||

|

The First Day |

|

||

house. I was seven years old at the time. Paul was seventeen years dead. His home resonated with the life he’d led, and when I stepped into it, his presence shifted and settled like the sound of someone breathing just beside me.

house. I was seven years old at the time. Paul was seventeen years dead. His home resonated with the life he’d led, and when I stepped into it, his presence shifted and settled like the sound of someone breathing just beside me. unchanged from the way it was the day Paul died; unvisited over the years, aside from the occasional hunter who bunked down there, and whoever it was took the family silver from it’s secret compartment beneath the kitchen sink. Paul still inhabited the place, all of his things were there—dishtowels and frying pans, medicines and books, photographs and bundles of letters received.

unchanged from the way it was the day Paul died; unvisited over the years, aside from the occasional hunter who bunked down there, and whoever it was took the family silver from it’s secret compartment beneath the kitchen sink. Paul still inhabited the place, all of his things were there—dishtowels and frying pans, medicines and books, photographs and bundles of letters received.